| The College Dropout | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Studio album by | |||

| Released | February 10, 2004 | ||

| Recorded | 1999–2003 | ||

| Studio |

| ||

| Genre | Hip hop | ||

| Length | 76:13 | ||

| Label | |||

| Producer |

| ||

| Kanye West chronology | |||

| |||

| Singles from The College Dropout | |||

| |||

- Kanye West College Dropout Vinyl

- Kanye West The College Dropout

- Kanye West The College Dropout Wiki

- Kanye West The College Dropout

- Kanye West The College Dropout Raritan Bay

The College Dropout is the debut studio album by American rapper and producer Kanye West. It was released on February 10, 2004, by Def Jam Recordings and Roc-A-Fella Records.

Producer Kanye West's highlight reels were stacking up exponentially when his solo debut for Roc-a-Fella was released, after numerous delays and a handful of suspense-building underground mixes. The week The College Dropout came out, three singles.

Kanye West College Dropout Vinyl

In the years leading up to the album, West had received praise for his production work for rappers such as Jay-Z and Talib Kweli, but faced difficulty being accepted as an artist in his own right by figures in the music industry. Intent on pursuing a solo career, he signed a record deal with Roc-A-Fella and recorded The College Dropout over a period of four years, beginning in 1999.

The album's production was primarily handled by West and developed his 'chipmunk soul' production style, which made use of sped-up, pitch shifted vocal samples from soul and R&B records, in addition to West's own drum programming, string accompaniments, and gospel choirs; it also features contributions from Jay-Z, Mos Def, Jamie Foxx, Syleena Johnson, and Ludacris, among others. Diverging from the then-dominant gangster persona in hip hop, West's lyrics concern themes of family, self-consciousness, materialism, religion, racism, and higher education.

The College Dropout debuted at number two on the US Billboard 200, selling 441,000 copies in its first week of sales. It was a massive commercial success, becoming West's best-selling album in the United States, with domestic sales of over 3.4 million copies by 2014. The album was promoted with singles such as 'Through the Wire', 'Jesus Walks', 'All Falls Down', and 'Slow Jamz', the latter two of which peaked within the top ten of the Billboard Hot 100.

A widespread critical success, The College Dropout was praised for West's production, humorous and emotional raps, and the music's balance of self-examination and mainstream sensibilities. It earned the rapper several accolades including a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album at the 2005 Grammy Awards. It has since been named by Time, Rolling Stone, and other publications as one of the greatest albums of all time.

- 6Critical reception

- 7Track listing

- 8Personnel

- 9Charts

Background[edit]

Kanye West began his early production career in the mid-1990s, making beats primarily for burgeoning local artists, eventually developing a style that involved speeding up vocal samples from classic soul records. For a time, he acted as a ghost producer for Deric 'D-Dot' Angelettie. Due to his association with D-Dot, West wasn't able to release a solo album, so he formed and became a member and producer of the Go-Getters, a late-1990s Chicago rap group composed of him, GLC, Timmy G, Really Doe, and Arrowstar.[1][2] The group released their first and only studio album World Record Holders in 1999.[1] West came to achieve recognition and is often credited with revitalizing Jay-Z's career with his contributions to the rap mogul's influential 2001 album The Blueprint.[3]The Blueprint has been named by Rolling Stone as the 252nd greatest album of all time and the critical and financial success of the album generated substantial interest in West as a producer.[4] Serving as an in-house producer for Roc-A-Fella Records, West produced records for other artists from the label, including Beanie Sigel, Freeway, and Cam'ron. He also crafted hit songs for Ludacris, Alicia Keys, and Janet Jackson.[3][5][6][7]

Although he had attained success as a producer, Kanye West aspired to be a rapper, but had struggled to attain a record deal.[6] Record companies ignored him because he did not portray the gangsta image prominent in mainstream hip hop at the time.[8] After a series of meetings with Capitol Records, West was ultimately denied an artist deal.[9] According to Capitol Record's A&R, Joe Weinberger, he was approached by West and almost signed a deal with him, but another person in the company convinced Capitol's president not to.[9] Desperate to keep West from defecting to another label, then-label head Damon Dash reluctantly signed West to Roc-A-Fella Records. Jay-Z, West's colleague, later admitted that Roc-A-Fella was initially reluctant to support West as a rapper, claiming that many saw him as a producer first and foremost, and that his background contrasted with that of his labelmates.[8][10]

West's breakthrough came a year later on October 23, 2002, when, while driving home from a California recording studio after working late, he fell asleep at the wheel and was involved in a near-fatal car crash.[11] The crash left him with a shattered jaw, which had to be wired shut in reconstructive surgery. The accident inspired West; two weeks after being admitted to a hospital, he recorded a song at the Record Plant with his jaw still wired shut.[11] The composition, 'Through the Wire', expressed West's experience after the accident, and helped lay the foundation for his debut album, as according to West 'all the better artists have expressed what they were going through'.[12][13] West added that 'the album was my medicine', as working on the record distracted him from the pain.[14] 'Through the Wire' was first available on West's Get Well Soon...mixtape, released December 2002.[15] At the same time, West announced that he was working on an album called The College Dropout, whose overall theme was to 'make your own decisions. Don't let society tell you, 'This is what you have to do.'[16]

Recording[edit]

West began recording The College Dropout in 1999, taking four years to complete.[17] Recording sessions took place at Record Plant in Los Angeles, California, but the production featured on the record took place elsewhere over the course of several years. According to John Monopoly, West's friend, manager and business partner, the album '...[didn't have] a particular start date. He's been gathering beats for years. He was always producing with the intention of being a rapper. There's beats on the album he's been literally saving for himself for years.' At one point, West hovered between making a portion of the production in the studio and the majority within his own apartment in Newark, New Jersey. Because it was a two-bedroom apartment, West was able to set up a home studio in one of the rooms and his bedroom in the other.[6]

West brought with him to the studio a Louis Vuitton backpack filled with old disks and demos to the studio, producing tracks in less than fifteen minutes at a time. He recorded the remainder of the album in Los Angeles while recovering from the car accident. Once he had completed the album, it was leaked months before its release date.[6] However, West decided to use the opportunity to review the album, and The College Dropout was significantly remixed, remastered, and revised before being released. As a result, certain tracks originally destined for the album were subsequently retracted, among them 'Keep the Receipt' with Ol' Dirty Bastard and 'The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly' with Consequence.[18] West meticulously refined the production, adding string arrangements, gospel choirs, improved drum programming and new verses.[6] On his personal blog in 2009, West stated he was most inspired by The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill and listened to the album everyday while working on The College Dropout.[19]

The song 'School Spirit' was censored for the album because Aretha Franklin would not allow the rapper to sample her music without censorship being promised.[20] It was revealed by Plain Pat that there were around three other versions of the song, but West disliked them. Pat said in reference to the Franklin sample: 'That song would have been so weak if we didn't get that sample cleared.'.[21] In 2011, an uncensored version of the track was distributed online.[22]

West finished recording around December 2003, according to his older cousin and singer Tony Williams, who was recruited by the rapper two weeks before the album's deadline to contribute vocals. Williams had impressed West by singing improvisations to 'Spaceship' during one of their drives together. The singer later recounted recording with West at the Record Plant: 'I get in, go in the booth, start vibing out on 'Spaceship' and finished it up. At that point he was like, 'Ok, Well let me see what you do on this song.' I think that's when we did 'Last Call.' One song lead to another, and by the end of the weekend, I was on like five songs. Then we did the 'I'll Fly Away' joint.'[23]

Music and lyrics[edit]

The College Dropout diverged from the then-dominant gangster persona in hip hop in favor of more diverse, topical subjects for the lyrics.[13] Throughout the album, West touches on a number of different issues drawn from his own experiences and observations, including organized religion, family, sexuality, excessive materialism, self-consciousness, minimum wage labor, institutional prejudice, and personal struggles.[24][25][26] Music journalist Kelefa Sanneh wrote, 'Throughout the album, Mr. West taunts everyone who didn't believe in him: teachers, record executives, police officers, even his former boss at the Gap'.[27] West explained, 'My persona is that I'm the regular person. Just think about whatever you've been through in the past week, and I have a song about that on my album.'[28] The album was musically notable for West's unique development of his 'chipmunk soul' production style,[29] in which R&B and soul musicsamples were sped up and pitch shifted.[30][31]

'Through the Wire' is an autobiographical song about West's 2002 car accident when he had to have his jaw wired shut. The track is representative of his production style, in which he samples and speeds up sections from classic soul records and uses them to create melodic hooks. | |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The album begins with a skit featuring a college professor asking West to deliver a graduation speech. The skit is followed by 'We Don't Care' featuring West comically celebrating drug life with lines like 'We wasn't supposed to make it past 25, joke's on you, we still alive' and then criticizing its influence amongst children.[27] The next track, 'Graduation Day', features Miri Ben-Ari on violin,[32] and vocals by John Legend.[33]

On 'All Falls Down', West wages an attack on consumerism.[5][34] The song features singer Syleena Johnson and contains an interpolation of Lauryn Hill's 'Mystery of Iniquity'.[33] West called upon Johnson to re-sing a vocal portion of 'Mystery of Iniquity', which ended up in the final mix.[35] Gospel hymn with doo-wop elements 'I'll Fly Away' precedes 'Spaceship', a track with a relaxed beat containing a soulful Marvin Gaye sample. The lyrics are mostly critical of the working world, where West muses about flying away in a spaceship to leave his boring job, and guest rappers GLC and Consequence add comparisons to modern day retail environment with slavery.[34]

On 'Jesus Walks', West professes his belief in Jesus, while also discussing how religion is used by various people and how the media seems to avoid songs that address matters of faith while embracing compositions on violence, sex, and drugs.[34][36] 'Jesus Walks' is built around a sample of 'Walk With Me' as performed by the ARC Choir.[33] Garry Mulholland of The Observer described it as a 'towering inferno of martial beats, fathoms-deep chain gang backing chants, a defiant children's choir, gospel wails, and sizzling orchestral breaks.'[37] The first verse of the song is told through the eyes of a drug dealer seeking help from God, and it reportedly took over six months for West to draw inspiration for the second verse.[38]

'Never Let Me Down' is influenced by West's near-death car crash. The song features Jay-Z who rhymes about maintaining status and power given his chart success, with West commenting about racism and poverty.[34][39] The song features verses by spoken word performer J. Ivy who offers comments of upliftment. 'Never Let Me Down' reuses a Jay-Z verse first heard in the remix of his song 'Hovi Baby'.[34][40] 'Get Em High' is a collaboration by West with two socially conscious rappers, Talib Kweli and Common.[41] 'The New Workout Plan' is a call to fitness to improve one's love life.[34] 'Slow Jamz' features Twista and Jamie Foxx and serves as a tribute to classic smooth soul artists and slow jam songs.[5] The song also appeared on Twista's album Kamikaze.[5] On the song 'School Spirit', West relates the experience of dropping out of school and contains references to well-known fraternities, sororities, singer Norah Jones, and record label Roc-A-Fella Records. 'Two Words' features commentary on social issues and features Mos Def, Freeway, and the Harlem Boys Choir.[42]

'Through the Wire' features a high-pitched vocal sample of Chaka Khan and relates West's real life experience with being in a car accident.[11] The song provides a mostly comedic account of his difficult recovery, and features West rapping with his jaw still wired shut from the accident.[11][33] The chorus and instrumentals sample a pitched up version of Chaka Khan's 1985 single 'Through the Fire'.[5] 'Family Business' is a soulful tribute to the godbrother of Tarrey Torae, one of the many collaborators in the album.[43] The song 'Last Call' is about West's transition from being a producer to a rapper, and the album ends with a nearly nine-minute autobiographical monologue that follows the song 'Last Call', however, is not a separate track.[44]

Title and packaging[edit]

The album's title is in part a reference to West's decision to drop out of college to pursue his dream of becoming a musician.[45] This action greatly displeased his mother, who was a professor at the university from which he withdrew. She later said, 'It was drummed into my head that college is the ticket to a good life... but some career goals don't require college. For Kanye to make an album called College Dropout it was more about having the guts to embrace who you are, rather than following the path society has carved out for you.'[46]

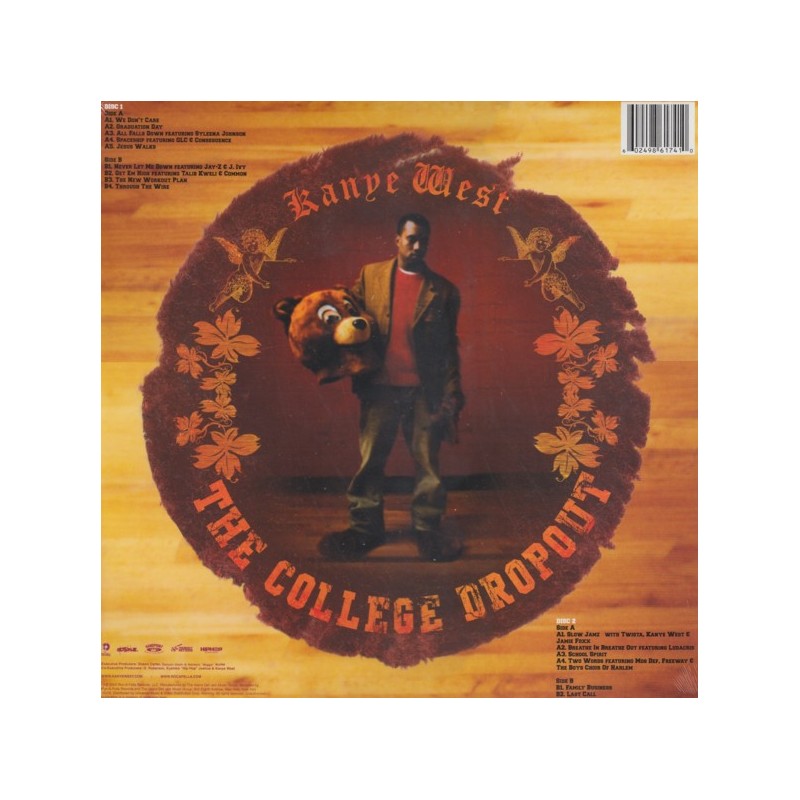

The artwork for the album was developed by Eric Duvauchelle, who was then part of Roc-A-Fella's in-house brand design team. West had already taken pictures dressed as the Dropout Bear - which would reappear in his later work - and Duvauchelle picked the image of him sitting on a set of bleachers, as he was attracted to the loneliness of what was supposed to be 'the most popular representation of a school'. The image is framed inside gold ornaments, which Duvauchelle found in a book of illustrations from the 16th-century and West wanted to use to 'bring a sense of elegance and style to what was typically a gangster-led image of rap artists'. The inside cover follows a college yearbook, with photos of the featured artists of the albums from their youth.[47]

Release and promotion[edit]

The College Dropout was originally scheduled for release in August 2003, but West's perfectionist habits producing the album led to it being postponed three times. It was first delayed to October 2003, then to January 2004, before finally being released to stores on February 10, 2004.[48][49]

In its first week of release, the album sold 441,000 copies and debuted at number two on the Billboard 200 chart, behind Norah Jones' Feels Like Home.[50] It remained on the second spot behind Feels Like Home for two more weeks, with 196,000 units sold in the second week and 132,000 in the third week.[51][52] In April, it was certified platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), indicating one million copies moved, and June 30 it was certified double Platinum.[53] By June 2014, The College Dropout had become West's best-selling album in the US, with domestic sales of 3,358,000 copies.[54][55] It has also sold over 4 million copies worldwide.[56] In 2004, The College Dropout was ranked as the twelfth most popular album of the year on the Billboard 200.[57] As of 2018 The College Dropout is the fourteenth highest selling rap album in the UK in the 21st-century.[58]

Four of the singles released in promotion of the album became top-20 chart hits: 'Through the Wire', 'Slow Jamz', 'All Falls Down', and 'Jesus Walks'.[59] 'The New Workout Plan' was the fifth and last single.[60] 'Spaceship' was planned to be the sixth single, but Def Jam decided to move on from The College Dropout's promotional campaign to begin marketing West's next album, Late Registration.[61] At one point, 'Two Words' was also intended to be released as a single, and a video for the song was filmed, and later uploaded by West online in 2009.[41]

Critical reception[edit]

| Professional ratings | |

|---|---|

| Aggregate scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 87/100[62] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [5] |

| Blender | [63] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[64] |

| Los Angeles Times | [65] |

| Mojo | [66] |

| Pitchfork | 8.2/10[3] |

| Rolling Stone | [67] |

| Spin | B+[68] |

| USA Today | [69] |

| The Village Voice | A[70] |

The College Dropout was met with widespread critical acclaim. At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream publications, the album received an average score of 87, based on 25 reviews.[62]

The record was hailed by Kelefa Sanneh from The New York Times as '2004's first great hip-hop album'.[27] Reviewing it for The A.V. Club, Nathan Rabin observed in the music 'substance, social commentary, righteous anger, ornery humanism, dark humor, and even Christianity', calling it 'one of those wonderful crossover albums that appeal to a huge audience without sacrificing a shred of integrity'.[71]Mojo said its exceptional hip hop production was miraculous during a time when hip hop's practice of sampling was becoming 'increasingly litigious',[66] and URB deemed it 'both visceral and emotive, sprinkling the dancefloors with tears and sweat'.[72] Dave Heaton from PopMatters found it 'musically engaging' and 'a genuine extension of Kanye's personality and experiences',[34] while Hua Hsu of The Village Voice felt that his sped-up samples 'carry a humble, human air', allowing listeners to 'hear tiny traces of actual people inside'.[73] Fellow Village Voice critic Robert Christgau wrote that 'not only does [West] create a unique role model, that role model is dangerous—his arguments against education are as market-targeted as other rappers' arguments for thug life'.[70] In the opinion of Stylus Magazine's Josh Love, West 'subverts cliches from both sides of the hip-hop divide' while 'trying to reflect the entire spectrum of hip-hop and black experience, looking for solace and salvation in the traditional safehouses of church and family'.[24]Entertainment Weekly's Michael Endelman elaborated on West's avoidance of the then-dominant 'gangsta' persona of hip hop:

West delivers the goods with a disarming mix of confessional honesty and sarcastic humor, earnest idealism and big-pimping materialism. In a scene still dominated by authenticity battles and gangsta posturing, he's a middle-class, politically conscious, post-thug, bourgeois rapper – and that's nothing to be ashamed of.[64]

Some reviewers were more qualified in their praise. Rolling Stone's Jon Caramanica felt that 'West isn't quite MC enough to hold down the entire disc',[67] while Slant Magazine's Sal Cinquemani observed 'too many guest artists, too many interludes, and just too many songs period' on what he considered a 'chest-beatingly self-congratulatory' yet humorous, deeply sincere, and affecting record.[25] It was regarded by Pitchfork critic Rob Mitchum as a 'flawed, overlong, hypocritical, egotistical, and altogether terrific album'.[3]Rolling Stone was more receptive in a retrospective review, calling the album 'a demonstration that hip-hop—real, banging, commercial hip-hop—could be a vehicle for nuanced self-examination and musical subtlety.'[74]

Accolades[edit]

The College Dropout was voted as the best album of the year by The Village Voice's Pazz & Jop, an annual poll of American critics.[75] The album elsewhere topped year-end lists by Rolling Stone,[76]Spin,[77] and PopMatters.[78] Dutch magazine OOR named it the seventh best album of 2004.[79]Billboard named The College Dropout the second best album of 2004.[80]Rhapsody named it the seventh best album of the decade and the fourth best hip hop album of the decade.[81][82]Fact listed it as the 20th best album of the 2000s.[83]

In 2005, Pitchfork named it No. 50 in their best albums of 2000–2004.[84] In 2006, the album was named by Time as one of the 100 best albums of all time.[85] In its retrospective 2007 issue, XXL awarded it a perfect 'XXL' rating, which had previously been given to only sixteen other albums.[86] In 2012, Complex named the album one of the classic albums of the last decade,[87] and the 20th best hip hop debut album ever.[88]Dagsavisen listed the album eleventh in its list of the top forty albums of the 2000s decade.[89] The album was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[90] Comedian Chris Rock has attested to listening to The College Dropout while writing his material.[91]

| Publication | Country | Accolade | Year | Rank | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The A.V. Club | United States | Top 50 Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 2 | [92] |

| BET | The Best Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 3 | [93] | |

| Consequence of Sound | The Top 100 Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 16 | [94] | |

| The Top 100 Albums Ever | 2010 | 100 | [95] | ||

| Entertainment Weekly | The 10 Best Albums of the Decade | 2009 | 1 | [96] | |

| The 100 Best Albums from 1983 to 2008 | 2008 | 4 | [97] | ||

| Newsweek | The 10 Best Albums of the Decade | 2009 | 3 | [98] | |

| Paste | The 50 Best Albums of the Decade (2000–2009) | 2009 | 17 | [99] | |

| Phoenix New Times | The 10 Best Rap Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 2 | [100] | |

| Pitchfork | The 200 Best Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 28 | [101] | |

| PopMatters | The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s | 2014 | 29 | [102] | |

| Rolling Stone | The 100 Greatest Debut Albums of All Time | 2013 | 19 | [103] | |

| The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time | 2012 | 298 | [104] | ||

| The 100 Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 10 | [105] | ||

| Clash | United Kingdom | The Top 100 Albums of Clash's Lifetime (2004–2012) | 2012 | 17 | [106] |

| NME | The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time | 2013 | 273 | [107] | |

| The Sunday Times | The 30 Best Albums of the 2000s | 2009 | 14 | [108] | |

| The Times | The 100 Best Pop Albums of the Noughties | 2009 | 13 | [109] |

Awards[edit]

| Year | Organization | Award | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | American Music Awards | Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Album | Nominated | [110] |

| Billboard Music Awards | R&B/Hip-Hop Album of the Year | Nominated | [111] | |

| MOBO Awards | Best Album | Won | [112] | |

| The Source Awards | Album of the Year | Won | [113] | |

| Teen Choice Awards | Album of the Year | Won | [114] | |

| 2005 | Grammy Awards | Album of the Year | Nominated | [115] |

| Best Rap Album | Won | |||

| NAACP Image Awards | Outstanding Album | Nominated | [116] |

Track listing[edit]

- Information is adapted from the album's liner notes.[33]

- All tracks produced by Kanye West, except 'Last Call' (co-produced by Evidence; additional production by Porse) and 'Breathe in Breathe Out' (co-produced by Brian 'All Day' Miller).

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 'Intro (Skit)' | Kanye West | 0:19 |

| 2. | 'We Don't Care' | 3:59 | |

| 3. | 'Graduation Day' |

| 1:22 |

| 4. | 'All Falls Down' (featuring Syleena Johnson) | 3:43 | |

| 5. | 'I'll Fly Away' | Albert E. Brumley | 1:09 |

| 6. | 'Spaceship' (featuring GLC and Consequence) |

| 5:24 |

| 7. | 'Jesus Walks' | 3:13 | |

| 8. | 'Never Let Me Down' (featuring Jay-Z and J. Ivy) |

| 5:24 |

| 9. | 'Get Em High' (featuring Talib Kweli and Common) | 4:49 | |

| 10. | 'Workout Plan (Skit)' | West | 0:46 |

| 11. | 'The New Workout Plan' |

| 5:22 |

| 12. | 'Slow Jamz' (featuring Twista and Jamie Foxx) | 5:16 | |

| 13. | 'Breathe in Breathe Out' (featuring Ludacris) |

| 4:06 |

| 14. | 'School Spirit (Skit 1)' | West | 1:18 |

| 15. | 'School Spirit' | 3:02 | |

| 16. | 'School Spirit (Skit 2)' | West | 0:43 |

| 17. | 'Lil Jimmy (Skit)' | West | 0:53 |

| 18. | 'Two Words' (featuring Mos Def, Freeway and The Boys Choir of Harlem) |

| 4:26 |

| 19. | 'Through the Wire' | 3:41 | |

| 20. | 'Family Business' | West | 4:38 |

| 21. | 'Last Call' |

| 12:40 |

| Total length: | 76:13 | ||

Kanye West The College Dropout

2005 Japanese special edition[edit]

| Bonus track | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 22. | 'Heavy Hitters' (featuring GLC) | 3:01 | |

| Total length: | 80:08 | ||

| Bonus CD | ||

|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Length |

| 1. | 'We Don't Care (Reprise)' (featuring Keyshia Cole) | 2:57 |

| 2. | 'Jesus Walks (Remix)' (featuring Mase and Common) | 4:58 |

| 3. | 'It's Alright' (featuring Ma$e and John Legend) | 3:51 |

| 4. | 'The New Workout Plan (Remix)' (featuring Fonzworth Bentley, Luke and Twista; produced by Lil Jon) | 4:02 |

| 5. | 'Two Words (Cinematic)' (featuring The Harlem Boys Choir) | 4:06 |

| 6. | 'Never Let Me Down (Cinematic)' | 5:16 |

| Total length: | 25:07 | |

| Bonus DVD: The College Dropout Video Anthology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Director(s) | Length |

| 1. | 'Through the Wire' |

| 4:54 |

| 2. | 'Slow Jamz' (performed by Twista featuring Kanye West and Jamie Foxx) | 3:34 | |

| 3. | 'All Falls Down' (featuring Syleena Johnson) |

| 4:05 |

| 4. | 'Two Words' (featuring Mos Def, Freeway and The Harlem Boys Choir) | 4:43 | |

| 5. | 'Jesus Walks' (Church version) | Michael Haussman | 4:04 |

| 6. | 'Jesus Walks' (Chris Milk version) | Milk | 4:06 |

| 7. | 'Jesus Walks' (Street version) |

| 4:18 |

| 8. | 'Jesus Walks' (Making of the video) | 66:56 | |

| 9. | 'The New Workout Plan' (Extended version featuring Fonzworth Bentley) | 8:06 | |

| Total length: | 104:46 | ||

Sample credits[edit]

- 'We Don't Care' contains samples of 'I Just Wanna Stop', written by Ross Vannelli and performed by The Jimmy Castor Bunch.

- 'All Falls Down' contains interpolations of 'Mystery of Iniquity', written and performed by Lauryn Hill.

- 'Spaceship' contains samples of 'Distant Lover', written by Marvin Gaye, Gwen Gordy Fuqua and Sandra Greene, and performed by Marvin Gaye.

- 'Jesus Walks' contains samples of 'Walk with Me', performed by The ARC Choir and '(Don't Worry) If There's a Hell Below, We're All Going to Go', written and performed by Curtis Mayfield.

- 'Never Let Me Down' contains samples of 'Maybe It's the Power of Love', written by Michael Bolton and Bruce Kulick, and performed by Blackjack.

- 'Slow Jamz' contains samples of 'A House Is Not a Home', written by Burt Bacharach and Hal David, and performed by Luther Vandross.

- 'School Spirit' contains samples of 'Spirit in the Dark', written and performed by Aretha Franklin.

- 'Two Words' contains samples of 'Peace & Love (Amani Na Mapenzi) – Movement IV (Encounter)', written by Lou Wilson, Ric Wilson and Carlos Wilson, and performed by Mandrill.

- 'Through the Wire' contains samples of 'Through the Fire', written by David Foster, Tom Keane and Cynthia Weil, and performed by Chaka Khan.

- 'Family Business' contains samples of 'Fonky Thang', written by Terry Callier and Charles Stepney, and performed by The Dells.

- 'Last Call' contains samples of 'Mr. Rockefeller', written by Jerry Blatt and Bette Midler, and performed by Bette Midler.

Personnel[edit]

Credits adapted from liner notes.[33][117]

Musicians[edit]

| Production[edit]

Design[edit]

|

Charts[edit]

Weekly charts[edit]

| Year-end charts[edit]

|

Certifications[edit]

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Canada (Music Canada)[127] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[128] | Gold | 7,500^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[129] | 2× Platinum | 600,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[131] | 3× Platinum | 3,358,000[130] |

*sales figures based on certification alone | ||

References[edit]

- ^ abBarber, Andrew (July 23, 2012). '93. Go-Getters 'Let Em In' (2000)'. Complex. Complex Media. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^Reid, Shaheem (September 30, 2005). 'Music Geek Kanye's Kast of Thousands'. MTV. MTV Networks. Retrieved April 23, 2006.

- ^ abcdMitchum, Rob (February 20, 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Pitchfork. Archived from the original on July 31, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^'500 Greatest Albums of All Time: #464 (The Blueprint)'. Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. November 18, 2003. Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ^ abcdefKellman, Andy. 'The College Dropout – Kanye West'. AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ abcdeReid, Shaheem (February 9, 2005). 'Road to the Grammys: The Making Of Kanye West's College Dropout'. MTV. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^Serpick, Evan. Kanye West. Rolling Stone Jann Wenner. Retrieved on December 26, 2009.

- ^ abHess, p. 556

- ^ abCalloway, Sway; Reid, Shaheem (February 20, 2004). 'Kanye West: Kanplicated'. MTV. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^Williams, Jean A (October 1, 2007). 'Kanye West: The Man, the Music, and the Message.(Biography)'. The Black Collegian. Archived from the original on January 25, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ abcdKearney, Kevin (September 30, 2005). Rapper Kanye West on the cover of Time: Will rap music shed its 'gangster' disguise?Archived February 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. World Socialist Web Site. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- ^Birchmeier, Jason (2007). 'Kanye West – Biography'. Allmusic. All Media Guide. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ^ abDavis, Kimberly. 'The Many Faces of Kanye West'Archived January 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (June 2004) Ebony.

- ^Davis, Kimberly. 'Kanye West: Hip Hop's New Big Shot'Archived January 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine (April 2005) Ebony.

- ^Kamer, Foster (March 11, 2013). '9. Kanye West, Get Well Soon... (2003) – The 50 Best Rapper Mixtapes'. Complex. Archived from the original on March 13, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- ^Reid, Shaheem (December 10, 2002). 'Kanye West Raps Through His Broken Jaw, Lays Beats For Scarface, LudacrisArchived December 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine'. MTV. Accessed October 23, 2007.

- ^Sarad (February 10, 2015). 'Today In Hip Hop History: Kanye West Drops His 'College Dropout' LP 11 Years Ago'. The Source. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^Patel, Joseph (June 5, 2003). 'Producer Kanye West's Debut LP Features Jay-Z, ODB, Mos Def'. MTV. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on October 26, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^'The College Dropout is EW's Top Album of the Decade'. KanyeUniverseCity. December 7, 2009. Archived from the original on February 8, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2019.

- ^'When Rap Lyrics Get Censored, Even on the Explicit Version'. Complex. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^'The Making of Kanye West's 'The College Dropout''. Complex. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^'Kanye West – School Spirit (Uncensored Version)'. Fake Shore Drive®. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- ^Martins, Jordan (April 19, 2010). 'Tony Williams of G.O.O.D. Music Talks Most Memorable Studio Sessions With Kanye'. Complex. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ abLove, Josh. Review: The College DropoutArchived September 15, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Stylus Magazine. Retrieved on July 23, 2009.

- ^ abCinquemani, Sal (March 14, 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on March 11, 2015. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^James, Jim (December 27, 2009). 'Music of the decade'. The Courier-Journal. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ abcSanneh, Kelefa (February 9, 2004). 'No Reading And Writing, But Rapping Instead'. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^'Kanye West Biography'. Artistdirect. Rogue Digital, LLC. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- ^UnrecordedArchived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^Sabotage TimesArchived February 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ^Burrell, Ian (September 22, 2007). 'Kanye West: King of rap'. The Independent. UK. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- ^'Hip-Hop Violinist' Preps Solo DebutArchived June 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Billboard.

- ^ abcdefThe College Dropout (Media notes). Kanye West. Roc-A-Fella Records. 2004.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ abcdefgHeaton, Dave (March 5, 2004). Kanye West: The College DropoutArchived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. PopMatters. Retrieved on August 25, 2011

- ^Hall, Rashaun (January 21, 2005). 'Kanye West Collaborating With Lauryn Hill on New LP'. MTV. Archived from the original on January 7, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2009.

- ^Jones, Steve (February 10, 2005). 'Kanye West runs away with 'Jesus Walks''. USA Today. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^Mulholland, Garry (August 15, 2004). ''Jesus Walks' by Kanye West'. The Observer. London. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^Calloway, Sway; Reid, Shaheem (February 20, 2004). 'Kanye West: Kanplicated'. MTV. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on April 6, 2009. Retrieved April 21, 2009.

- ^''Watch The Throne': Jay-Z and Kanye West's 10 Best Collaborations'. Billboard. August 6, 2011. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^Batey, Angus (February 20, 2004). Kanye West – The College Dropout. Yahoo! Music. Retrieved on August 25, 2011

- ^ abReid, Shaheem (January 21, 2004). 'Common, John Mayer Drop in to Preview Kanye West's Dropout'. MTV. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^Ryan, Chris. Review: The College DropoutArchived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Spin. Retrieved on December 26, 2009.

- ^Ahmed, Isanul. '15 Things You Didn't Know About Kanye West's 'The College Dropout''. complex.com. Complex. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^Barber, Andrew. 'The 100 Best Kanye West Songs: 24. Kanye West 'Last Call' (2004)'. Complex Music. Complex Media. Archived from the original on June 30, 2014. Retrieved January 25, 2014.

- ^West, Donda, p. 106

- ^Hess, p. 558

- ^Pasori, Cedar; McDonald, Leighton (June 17, 2013). 'The Design Evolution of Kanye West's Album Artwork: The College Dropout'. Complex. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^Goldstein, Hartley (December 5, 2003). 'Kanye West: Get Well Soon / I'm Good'. PopMatters. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- ^Ahmed, Insanul (September 21, 2011). 'Kanye West × The Heavy Hitters, Get Well Soon (2003) – Clinton Sparks' 30 Favorite Mixtapes'. Complex. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^Martens, Todd (February 18, 2004). 'More Than A Million Take Norah 'Home''. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^Martens, Todd (February 25, 2004). 'Jones Remains At 'Home' At No. 1'. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^Martens, Todd (March 3, 2004). 'Norah Makes Comfy 'Home' At No. 1'. Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- ^Gold & Platinum: Searchable DatabaseArchived January 7, 2013, at WebCite. Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved on December 26, 2009.

- ^Grein, Paul (June 24, 2014). 'USA: Top 20 New Acts Since 2000'. Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ^Cibola, Marco (June 14, 2013). 'Kanye West: How the Rapper Grew From 'Dropout' to 'Yeezus''. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^Columnist. Mr Confidence puts it all on the lineArchived October 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Sun-Herald (August 1, 2005). Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ ab'Kanye West – Chart history'. Billboard. Archived from the original on March 9, 2015. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^'The UK's Official Top 40 biggest rap albums of the Millennium revealed'. Official Charts Company. May 4, 2018. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved July 10, 2019.

- ^'Does Kanye West's 'The College Dropout' Stand the Test of Time?'. The Boombox. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^'Kanye West's 'The New Workout Plan': Revisit His Hilariously Brilliant 'College Dropout' Single'. Idolator. Retrieved October 27, 2018.

- ^Kanye West's Lost 'Spaceship' Video | Kanye WestArchived June 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Rap Basement Retrieved July 1, 2012

- ^ ab'Reviews for College Dropout by Kanye West'. Metacritic. Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^Pareles, Jon (April 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Blender. New York (25): 124. Archived from the original on April 9, 2005. Retrieved July 4, 2016.

- ^ abEndelman, Michael (February 13, 2004). 'The College Dropout'. Entertainment Weekly. New York. Archived from the original on January 13, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^Baker, Soren (February 12, 2004). 'You'll know his name'. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^ ab'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Mojo. London (126): 102. May 2004.

- ^ abCaramanica, Jon (March 14, 2004). 'The College Dropout'. Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on December 20, 2010. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^Ryan, Chris (November 2003). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. Spin. New York. 19 (11): 111–12. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^Jones, Steve (February 9, 2004). ''Dropout': Well schooled'. USA Today. McLean. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ abChristgau, Robert (March 9, 2004). 'Edges of the Groove'. The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^Rabin, Nathan (February 17, 2004). 'Kanye West: The College Dropout'. The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved December 26, 2009.

- ^'Kanye West, 'The College Dropout' (Roc-A-Fella/Def Jam)'. URB. Los Angeles (114): 111. March 12, 2004.

- ^Hsu, Hua (February 10, 2004). 'The Benz or the Backpack?'. The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- ^'Kanye West: Album Guide'. Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on December 5, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2012.

- ^'Pazz & Jop 2004'. The Village Voice. October 18, 2005. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^White, Julian. 'Rolling Stone 2004 Critics'. RocklistMusic.co.uk. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^Staff. '40 Best Albums of the Year: 1) The College Dropout'. Spin. p. 68. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2005.

- ^'Top 100 Albums of 2004'. PopMatters. Archived from the original on January 7, 2005. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^'Jaarlijst Oor 2004' (in Dutch). Muzieklijstjes. Archived from the original on June 3, 2017. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^'Billboard 2004 – The Year in Music'. Billboard. Archived from the original on February 3, 2005. Retrieved August 11, 2019.

- ^Rhapsody Editorial (December 4, 2009). 'Rhapsody's 100 Best Albums of the Decade'. Rhapsody. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- ^Chennault, Sam (October 31, 2009). 'Hip-Hop's Best Albums of the Decade'. Rhapsody. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^'The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s'. Fact. Archived from the original on April 24, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^Pitchfork staff (February 7, 2005). 'The Top 100 Albums of 2000–04'. Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 9, 2010. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^'Time 100 Best Albums of All Time'. Time. November 2, 2006. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^XXL (December 2007). 'Retrospective: XXL Albums'. XXL.

- ^Drake, David. '25 Rap Albums From the Past Decade That Deserve Classic Status: Kanye West, The College Dropout (2004)'. Complex. Archived from the original on December 9, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ^'The 50 Greatest Debut Albums in Hip-Hop History: 20. Kanye West, The College Dropout'. Complex. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2012.

- ^'Top 40 Albums of the 2000s'. Dagsavisen (in Danish). November 24, 2009. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (February 7, 2006). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN0-7893-1371-5.

- ^'Why You Can't Ignore Kanye'. Time. August 21, 2005. Archived from the original on August 11, 2010. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^'Top 50 Albums of the 2000s'. The A.V. Club. November 19, 2009. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'Best Albums of 2000s'. BET. Archived from the original on December 29, 2009. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'CoS Top of the Decade: The Albums'. Consequence of Sound. November 17, 2018. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'Consequence of Sound's Top 100 Albums Ever'. Consequence of Sound. September 15, 2010. Archived from the original on February 26, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'10 Best Albums of Decade'. Entertainment Weekly. December 3, 2009. Archived from the original on March 24, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^Stosuy, Brandon (June 20, 2008). 'EW's 100 Best Albums From 1983 To 2008'. Stereogum. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^Colter Walls, Seth. 'Best Albums – The College Dropout Kanye West (2004)'. Newsweek. Archived from the original on July 31, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^'The 50 Best Albums of the Decade (2000-2009)'. Paste. November 2, 2009. Archived from the original on March 2, 2011. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^Chelsler, Josh. '10 Best Rap Albums of the 2000s'. Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^'The 200 Best Albums of the 2000s'. Pitchfork. October 2, 2009. Archived from the original on July 30, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s'. PopMatters. October 8, 2014. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'The 100 Best Debut Albums of All Time'. Rolling Stone. March 22, 2013. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'500 Greatest Albums of All Time'. Rolling Stone. May 31, 2015. Archived from the original on March 31, 2018. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'The 100 Best Albums of the 2000s'. Rolling Stone. July 18, 2011. Archived from the original on July 1, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^Diver, Mike (January 7, 2015). 'The Top 100 Albums Of Clash's Lifetime'. Clash. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'NME: The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time : October 2013'. Rocklist. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2019.

- ^'The Times – Best Album Of The Decade 2000 – 2009'. Rocklistmusic. Archived from the original on July 18, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^'The 100 best pop albums of the Noughties'. The Times. November 21, 2009. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^'32nd American Music Awards Nominees'. Billboard. September 14, 2004. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'2004 Billboard Music Awards Finalists'. Billboard. November 30, 2004. Archived from the original on November 12, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'MOBO Awards 2004 Winners'. MOBO. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'Kanye triumphs at Source awards'. BBC. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on December 18, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'Kanye triumphs at Source awards'. BBC. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on December 18, 2017. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^'Grammy Awards 2005: Key winners'. BBC. February 14, 2005. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2019.

- ^Rashbaum, Alyssa (January 20, 2005). 'Usher Scores Five Nominations For NAACP Image Awards'. MTV. Archived from the original on May 5, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- ^'Credits: The College Dropout'. AllMusic. All Media Guide. April 2, 2004. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- ^'Lescharts.com – Kanye West – The College Dropout'. Hung Medien.

- ^'Offiziellecharts.de – Kanye West – The College Dropout' (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts.

- ^'Swedishcharts.com – Kanye West – The College Dropout'. Hung Medien.

- ^'Official Albums Chart Top 100'. Official Charts Company.

- ^'Kanye West Chart History (Billboard 200)'. Billboard.

- ^'Kanye West Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)'. Billboard.

- ^'Kanye West Chart History (Top Rap Albums)'. Billboard.

- ^'2004 Year-End Charts – Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop Albums'. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on December 5, 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^'2005 Year-End Charts - Billboard R&B/Hip-Hop Albums'. Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on July 19, 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2015.

- ^'Canadian album certifications – Kanye West – The College Dropout'. Music Canada.

- ^Dec'Latest Gold / Platinum Albums'. RadioScope New Zealand. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^'British album certifications – Kanye West – The College Dropout'. British Phonographic Industry.Select albums in the Format field.Select Platinum in the Certification field.Type The College Dropout in the 'Search BPI Awards' field and then press Enter.

- ^Grein, Paul (June 24, 2014). 'USA: Top 20 New Acts Since 2000'. Yahoo! Music. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015.

- ^'American album certifications – Kanye West'. Recording Industry Association of America.If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH.

Bibliography[edit]

- Brown, Jake (2006). Kanye West in the Studio: Beats Down! Money Up! (2000–2006). Colossus Books. ISBN0-9767735-6-2.

- Hess, Mickey (2007). Icons of Hip Hop: an Encyclopedia of the Movement, Music, and Culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN0-313-33904-X.

- West, Donda; Hunter, Karen (2007). Raising Kanye: Life Lessons from the Mother of a Hip-Hop Superstar. Simon & Schuster. ISBN1-4165-4470-4.

External links[edit]

Kanye West The College Dropout Wiki

- The College Dropout at Discogs

Kanye West The College Dropout

Producer Kanye West's highlight reels were stacking up exponentially when his solo debut for Roc-a-Fella was released, after numerous delays and a handful of suspense-building underground mixes. The week The College Dropout came out, three singles featuring his handiwork were in the Top 20, including his own 'Through the Wire.' A daring way to introduce himself to the masses as an MC, the enterprising West recorded the song during his recovery from a car wreck that nearly took his life -- while his jaw was wired shut. Heartbreaking and hysterical ('There's been an accident like Geico/They thought I was burnt up like Pepsi did Michael'), and wrapped around the helium chirp of the pitched-up chorus from Chaka Khan's 'Through the Fire,' the song and accompanying video couldn't have forged his dual status as underdog and champion any better. All of this momentum keeps rolling through The College Dropout, an album that's nearly as phenomenal as the boastful West has led everyone to believe. From a production standpoint, nothing here tops recent conquests like Alicia Keys' 'You Don't Know My Name' or Talib Kweli's 'Get By,' but he's consistently potent and tempers his familiar characteristics -- high-pitched soul samples, gospel elements -- by tweaking them and not using them as a crutch. Even though those with their ears to the street knew West could excel as an MC, he has used this album as an opportunity to prove his less-known skills to a wider audience. One of the most poignant moments is on 'All Falls Down,' where the self-effacing West examines self-consciousness in the context of his community: 'Rollies and Pashas done drive me crazy/I can't even pronounce nothing, yo pass the Versacey/Then I spent 400 bucks on this just to be like 'N*gga you ain't up on this'.' If the notion that the album runs much deeper than the singles isn't enough, there's something of a surprising bonus: rather puzzlingly, a slightly adjusted mix of 'Slow Jamz' -- a side-splitting ode to legends of baby-making soul that originally appeared on Twista's Kamikaze, just before that MC received his own Roc-a-Fella chain -- also appears. Prior to this album, we were more than aware that West's stature as a producer was undeniable; now we know that he's also a remarkably versatile lyricist and a valuable MC.

Kanye West The College Dropout Raritan Bay

| Sample | Title/Composer | Performer | Time | Stream |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 00:19 | |||

| 2 | 03:59 | |||

| 3 | 01:22 | |||

| 4 | Lauryn Hill / Kanye West | 03:43 | ||

| 5 | 01:09 | |||

| 6 | L.D. Harris / Kanye West | 05:24 | ||

| 7 | 03:13 | |||

| 8 | 05:24 | |||

| 9 | 04:49 | |||

| 10 | 00:46 | |||

| 11 | 05:22 | |||

| 12 | Burt Bacharach / C.C. Mitchell / Kanye West | feat: Twista | 05:16 | |

| 13 | B. Miller / Kanye West | 04:06 | ||

| 14 | 01:18 | |||

| 15 | Aretha Franklin / Kanye West | 03:02 | ||

| 16 | 00:43 | |||

| 17 | 00:53 | |||

| 18 | 04:26 | |||

| 19 | Tom Keane / Cynthia Weil / Kanye West | 03:41 | ||

| 20 | 04:38 | |||

| 21 | 12:40 |